Building a 50ms Home Feed — Part 2: Implementation

From Design to Code: Building Homelander

The plan was ready; now it was time to build. This part covers how we implemented Homelander—rewriting core logic in Go, optimising database access, and rolling out the ETag and CDC systems that made the 50 ms home feed possible.

Target Implementation

As our system continued to scale, we realised that our existing Django-based architecture was no longer meeting performance demands—especially for the highly dynamic home screen rendering process. To address these challenges, we built a new Golang service called Homelander, which directly accesses the monolith’s database while focusing only on the specific tables required to render Home.

Yes—by traditional service boundary standards, this was a design violation. Homelander directly querying another service’s database is generally discouraged, as it couples two systems at the data layer. However, in our context, this trade-off was intentional and pragmatic. The home feed’s performance needs were extreme, and duplicating or syncing data through additional APIs or event pipelines would have added unacceptable latency and operational overhead. By carefully scoping Homelander’s access to read-only queries on a well-defined subset of tables, we preserved data consistency while unlocking the performance required to meet our sub-50 ms goal.

Rewriting Logic from Django to Go

We decided to migrate the core logic from Django to Golang for several reasons:

Improved Concurrency Handling:

We utilized singleflight to handle concurrent API requests that require the same database query. This significantly reduced the number of duplicate calls hitting our database.

Controlled Database Access:

By using pgx v5 directly (instead of an ORM or generic SELECT * queries), we gained tight control over query execution. It also allowed us to map database rows directly into Go structs, avoiding redundant memory copies that occur in ORM layers.

In-Memory Context Store:

We built an in-memory store that attaches both user and common data to the request context. Once a piece of data is fetched from the database, it’s cached within the same request lifecycle to avoid redundant lookups — for example, when multiple downstream calls require the same user record. This eliminates one class of N+1 query issues, particularly those caused by repeated access to identical objects. However, it doesn’t replace the need for explicit prefetching or batched queries when fetching related entities (e.g., fetching all users linked to a set of payments).

Performance Boost:

Golang’s concurrency model and lower overhead (compared to Python/Django) naturally delivered faster response times.

Validating the New Service

Before fully switching to Homelander, we ran extensive tests to ensure the service was functionally equivalent to the old system:

- Limited Rollout: We initially released Homelander to a small percentage of users to verify its behavior in a production environment. We made use of cloudflare DNS which helped in rewriting the hostname to homelander’s URL that way without any app update we were able to understand if the APIs were backward compatible and worked properly with the existing app builds.

- Parity Checks: Over the course of a day, we compared Homelander’s responses to those from the Django service for 500,000 users. This helped us confirm that both systems produced identical results for real-world scenarios.

After confirming business logic parity, we rolled out Homelander to all users at full scale. The results were immediately impressive:

- p90 Server-Side Latency of ~49 ms: A major improvement over the previous 2–4 second response times. This figure reflects backend processing time, not end-to-end user-perceived latency, which can vary based on network conditions and client-side rendering.

- Reduced Load: Singleflight and in-flight caching dramatically cut the volume of redundant database queries.

- With this our monolith service (Westeros) also needed less EC2s to host the servers and the buffer of resource limits increased for redis and postgres both.

Implementing the ETag System

Following Homelander’s successful launch, the final Etag logic has to be implemented:

- ETag Generation:

- On each request if we do not get the ETag from the client, the server generates an ETag which is actually a ULID

- We added a new header key:

Accept-Etagif this is sent with true by the client then only homelander will attach an etag and return the tag as well. This helps us roll it out in a controlled manner and understand if system is working as intended.

- Time-Based Invalidation:

- For any time-based invalidation vectors, if the remaining time is less than 24 hours, we reduce the overall ETag’s TTL accordingly.

- This ensures that time-sensitive data doesn’t remain cached beyond its validity window.

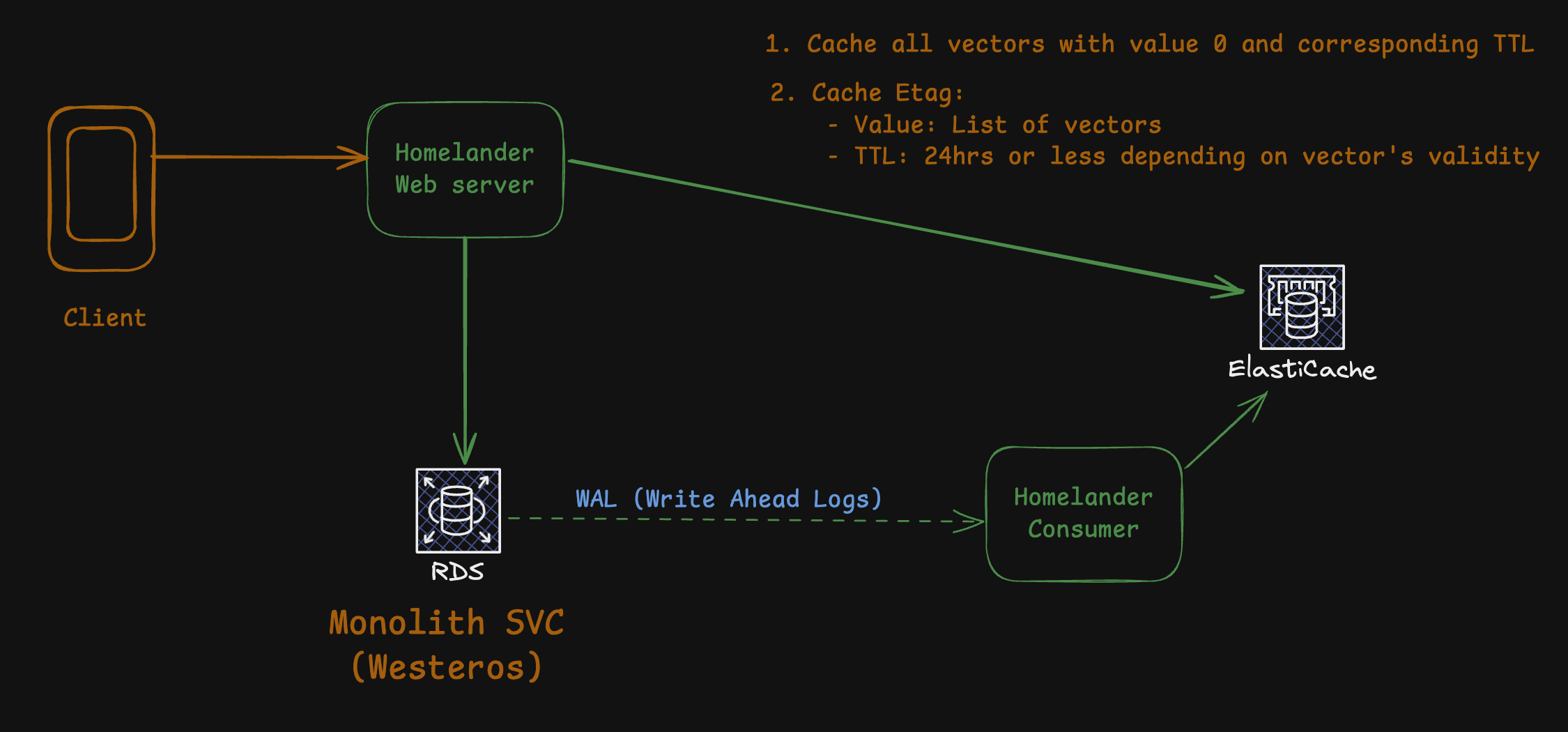

- Caching the ETag and Invalidation Vectors:

- At the end of request processing, we store the ETag with a list of its invalidation vectors.

- Each invalidation vector is cached individually, initially set to a value of 0 (representing a “valid” state).

Implementation of WAL consumer

To keep the ETag cache accurate, we rely on PostgreSQL’s Write-Ahead Log (WAL) for Change Data Capture (CDC). A separate WAL consumer service processes these logs and updates invalidation vectors:

- Detecting Changes:

- The WAL consumer listens for changes to tables that affect or represent invalidation vectors.

- When it detects an update or insert that invalidates a particular vector (e.g., a user’s KYC status changes), it sets the vector’s cached value to the current timestamp.

- We built our custom WAL consumer using the pglogrepl library, taking inspiration from PeerDB ’s approach to streaming data pipelines. Over time, we also developed our own lightweight library wal-e, to simplify WAL consumption and make integration easier across services.

- Checking ETag Validity:

- On subsequent requests, Homelander compares the timestamp in the ETag’s ULID against the updated timestamp of the invalidation vector.

- If the vector’s timestamp is greater than the ETag’s, it indicates the data is stale, and Homelander re-renders the response and issues a new ETag.

- If it is not greater, the system returns 304 Not Modified, allowing the client to use its cached content.

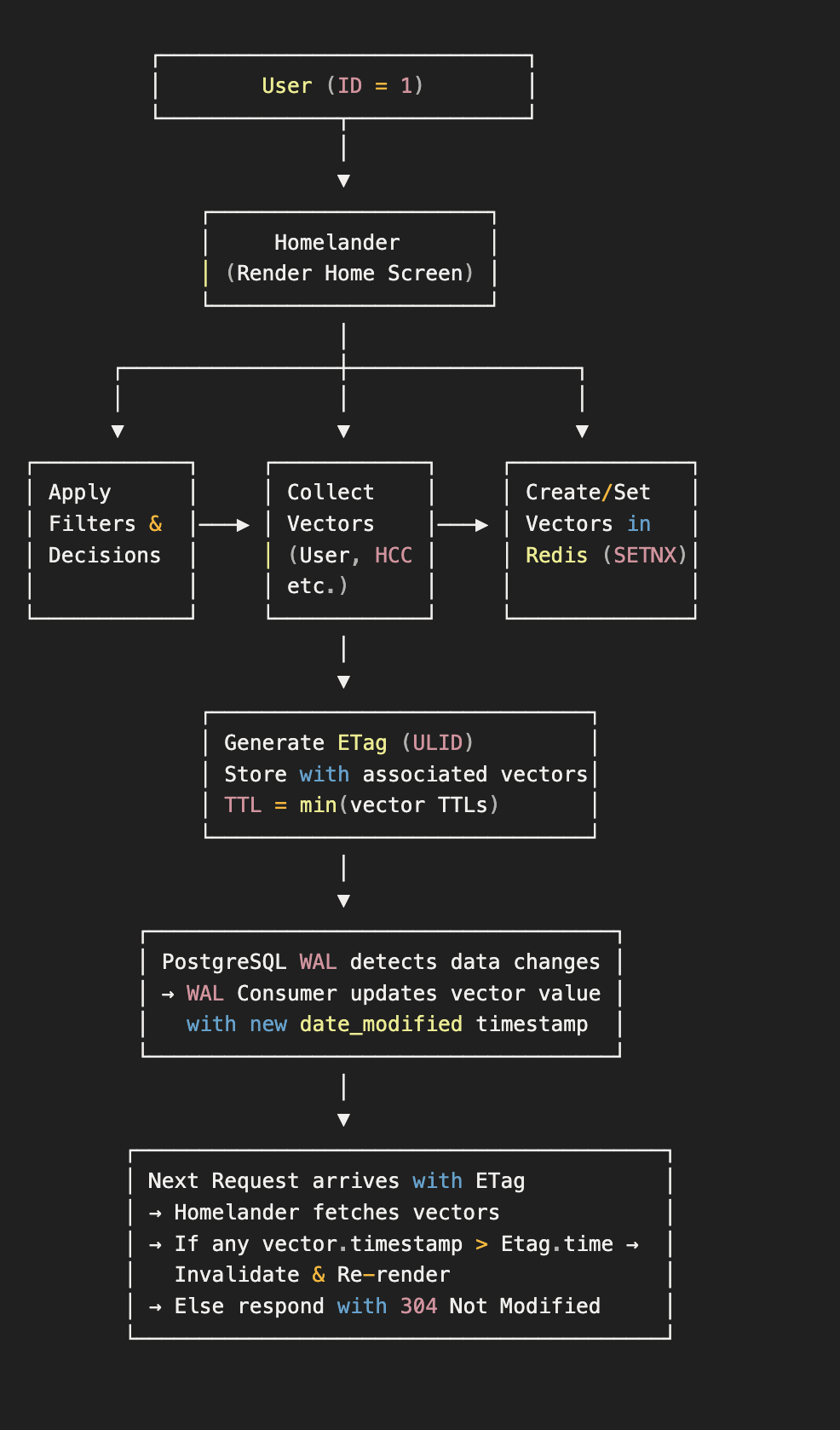

Lets take an example of how this logic would work in its entirety:

- Request Initiation:A user with ID

1sends a request to Homelander to render their home screen. - Rendering and Vector Collection:Homelander begins rendering the home page, applying various filters and logic to decide which cards should be shown to the user. During this process, it collects all the invalidation vectors involved in those decisions (for example, user attributes, feature flags, or campaign configurations).

- Vector Registration in Redis:Once rendering is complete, Homelander registers each collected vector in Redis using

SETNX.- If a vector doesn’t exist, it is created with an initial value of

0(indicating a valid state).

- If a vector doesn’t exist, it is created with an initial value of

- ETag Generation:Homelander then generates a unique ETag (a ULID) for this rendered response and stores it in Redis along with the list of associated vectors.

- The ETag’s TTL is set to the minimum TTL among its vectors to ensure consistency.

- Change Detection via WAL:When any relevant change occurs in the database (for example, a user’s record or card configuration is updated), the WAL consumer detects it and updates the corresponding vector’s value in Redis to the latest

date_modifiedtimestamp. - Subsequent Request Handling:When a subsequent request arrives with an existing ETag:

- Homelander first checks if the ETag exists in the cache. If not, it re-renders the page and generates a new one.

- If the ETag is found, it retrieves all associated vectors.

- If any vector’s timestamp is greater than the one associated with the ETag, the ETag is considered invalid, and the response is re-rendered. Otherwise, the cached version is returned with a 304 Not Modified response.

Visualisation:

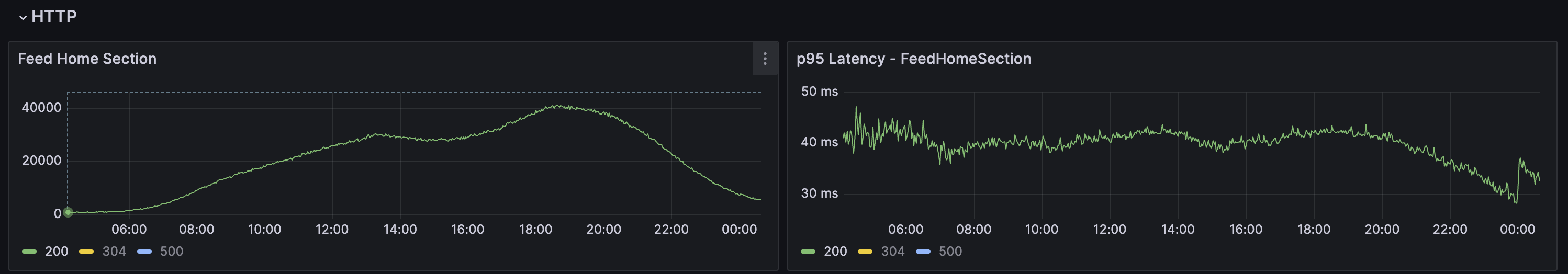

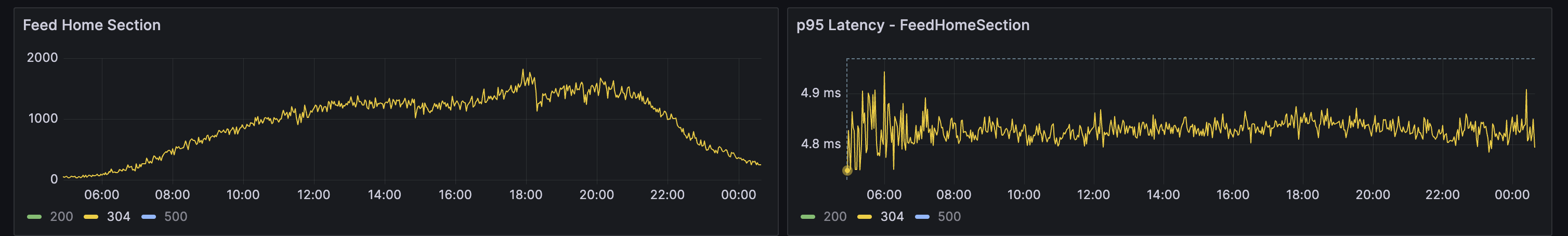

⚡️ Measuring the Impact: From Optimised 200s to Near-Instant 304s

These metrics represent 200 OK responses, where the home feed is fully recomputed and rendered on the server. Despite executing the complete rendering pipeline, p95 latency consistently stays under ~50 ms, reflecting the efficiency gains from Homelander’s architecture and query optimisations.

These metrics show 304 Not Modified responses, where the server validates the request using ETags and instructs the client to reuse its cached home feed. Since no re-rendering is required, this path avoids almost all computation, resulting in p95 latencies under ~5 ms. Additionally, because the client already has a cached response, the app can render the home feed almost instantly on startup. If any changes are detected, the feed is re-rendered making the overall experience feel significantly more responsive and snappy.

🚀 Wrapping Up

With Homelander, we transformed one of the most performance-critical parts of our app—its home feed—into a lightning-fast, scalable, and resilient system. By combining architectural shifts, smart caching using ETags, and CDC-based invalidation via PostgreSQL WAL logs, we reduced load times from several seconds to under 50ms.

Our approach ensured that flexibility wasn't sacrificed for speed. Product teams can still iterate freely, while engineering benefits from a lean, efficient backend.

In the coming weeks, we’ll be rolling out the ETag strategy to our clients and sharing performance insights from that launch—stay tuned for those updates!

🔮 What’s Next?

The home screen is just the beginning. Rendering it involves fetching multiple pieces of data from the backend to display up-to-date information to users. Currently, many of these supporting APIs are outside the Homelander service.

Looking ahead, we plan to gradually migrate all such APIs to Homelander and power them with the ETag caching model. This will allow us to avoid repeated data fetches and further streamline our infrastructure—pushing us closer to a consistently fast and efficient user experience across the board.

We also plan to evolve the ETag mechanism itself. Today, it operates in an “all-or-nothing” mode—any change invalidates the entire response. Our next goal is to enable partial cache reuse, where unchanged sections of the response continue to be served from cache, and only modified components are re-rendered.

📝 Acknowledgements

This work wouldn’t have been possible without the contributions of a few people who played a pivotal role in shaping Homelander.

Amarender Singh laid the foundation for this project and helped take it from idea to reality. He set a high bar for how Go services should be designed and written within the company, and his emphasis on clean, elegant engineering motivated the rest of us to build the system the right way.

Pratik Gajjar brought deep design clarity to the project. His fundamental thinking around caching and invalidation led to the ETag-based approach that became central to the system, and his ability to simplify complex problems was instrumental in making the architecture both robust and efficient.